Over the Easter weekend I went on my first overnight tramp in New Zealand. After living here nearly 7 years and professing a love for hiking and the outdoors that somehow never seems to have developed into significant time in the wilderness, this was quite momentous. It was all thanks to a friend of mine who has decades of experience with this sort of thing and did all the planning, so all I needed to do was turn up and tough it out. It was an amazing, life-affirming time and I’d like to share some thoughts, reflections and photos, including my near-death-experience.

Tramping ≠ hiking

I’ve always loved learning new languages and picking up dialect words in the various versions of English I’ve come across. I find it fascinating when I learn a word in another language that has no direct translation in English and I’m obviously not the only one as English is notorious for absorbing foreign words, from keeping both the pig of the Anglo Saxons and the pork of the Normans, to adding the “Weltschmerz” of the Germans. But when it comes to dialect, we can often be tricked into thinking it’s just another word for the same thing: tramping is surely just a different word for hiking?

Well no, no it’s not. The first thing I learned on my trip was that the kiwi dialect word tramping cannot be directly translated to hiking or walking as I have known it in other countries. Going for a walk or a hike in the UK, for example, generally involves well maintained and signed paths, with rivers and even streams crossed by bridges. On a hike, you’re rarely very far from civilisation and even if you’re not dodging a crowd of other people out to get some fresh air, you’re unlikely to go for more than an hour without meeting other walkers. There are certainly some more challenging hikes and even a couple of mountains for the more adventurous, but it’s a completely different experience to a “tramp”.

Our tramp did involve some beautifully maintained tracks and impressive suspension bridges. But a lot of our track went over and under fallen trees, through bogs that would put the Peak District to shame, and through river crossings where the bridges had either washed out or never existed, and where the water came up to my thighs. There were gorges where a mudslide had taken out the track so we had to scramble hesitantly over crumbling rock and slippery soil, then bash our way through the undergrowth on the other side to find the track. There were vines that tried to simultaneously throttle and trip us, a sneaky little plant called a bush lawyer that gripped onto clothes and skin with teeny tiny thorns. There was fern forest so dark we should’ve got our torches out. And most significantly, there was no such thing as a flat path.

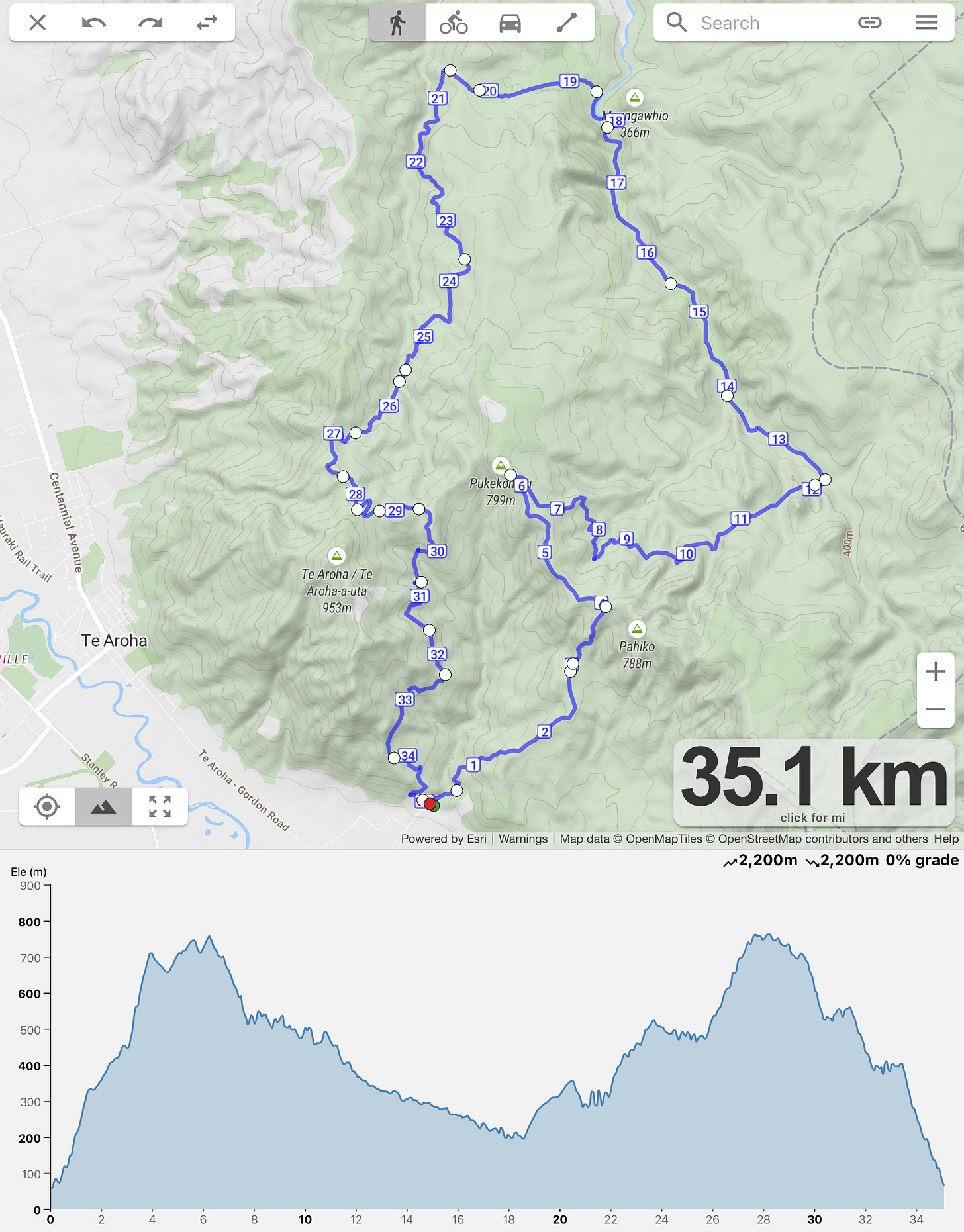

The first day alone involved climbing a total number of metres almost exactly equal to the height of Yr Wyddfa / Snowden, Britain’s second highest peak. Overall, we climbed 2,200m over three days and came down the same number, during which time I discovered a whole new world of pain as my left knee decided to seize up. Apparently all my running and weight lifting is as nothing compared to simply walking downhill with a pack on my back.

This all led me to my own personal definition of tramping: a hike in the bush which is measured in hours rather than kilometres, but is ultimately incredibly rewarding. Because it can quite literally take an hour to travel a single kilometre, but wow, it feels like more of an achievement than a 10k run.

Action movies have not lied to me

The other thing that tramping involves is paths, laughably called “pack horse trails”, that are barely wide enough for a human foot, hugging the contours of banks that are only just this side of cliffs. It was while navigating one of these that I had my near-death-experience. Or at the least, near-serious-injury experience. I put my foot down only to have the path melt away under me.

I remember green, lots of green, rolling, falling and scuffing as I tried to grab all the vegetation around me and have it all follow me down the gravity well. I had enough time for a thought to flash through my mind along the lines of “In an action movie, there’s always a tree to grab onto” before I finally found myself dangling off said tree. I’ve no memory of how I grabbed it, just that I did, and was now hanging over a drop of a few metres to a rocky creek below.

Adrenaline and the stress response are perfectly suited to crisis

The best thing about this incident was how wonderfully calm I felt in the moment and how amazing it was, looking back on it, to see my stress and adrenaline response working perfectly. As I hung from the tree, pack on my back, and thought how handy it was that the tree was there, my friend began the careful process of checking I was ok and finding her way down to me. I don’t know if it’s my inherent optimism, a side effect of adrenaline, a deep trust in the friend who I knew was trained and experienced in search and rescue, but I felt perfectly fine. My brain, which is normally spinning madly with all the things that could go wrong or need planning for, was completely focused and strangely relaxed. I wasn’t panicking and making bad decisions, I was calm and slow and content to deal with everything as it happened.

Afterwards, I couldn’t help comparing how the stress response works so perfectly for the experiences it’s designed for (i.e. dealing with immediate physical threats) with how terribly it works in the majority of stress-inducing experiences we deal with in normal life. In my day-job I lecture about this of course, about how the stress response is ill suited to our modern stressors at work, how we need to learn to manage it etc. But as with everything, a real experience brings all that theory home. And stress is very much on mind at the moment as I am currently on stress leave from work. Taking this sick leave is not a decision I took lightly. As I’ve mentioned before, it is hard to admit I just can’t cope with what looks like a relatively stress-free job.

I know any other academics reading this will understand the pressures of our work, but from the outside, our jobs do look quite ideal. We have a substantial amount of autonomy. Within certain very generous constraints, I can choose what I teach and how, what I research and how, and of course where and when I work. The downside to this is that there are no clear and fair performance criteria, practically zero feedback or reward for good work, and significant challenges in building supportive collegial relationships. And these are essential resources that we all need if we’re to be engaged in and perform well in our jobs.

Add to this that I actually love what I do and have a significant internal drive to do it well, and you can probably see how I’m almost pre-programmed to run myself into the ground. There is always more to do, There are always more and better ways to teach and more and better things to research. There are always more students needing help or wanting to learn more, always more colleagues to support. And never anyone saying “that’s good” or “well done” or even just “that’s enough, you can have a break now”. So I’m having to learn to say that to myself, which is difficult when for years, pushing myself has been the way to succeed.

That’s the problem with the stress response: it’s built for immediate, instant reaction, not for long-lasting, low-level threats. Hanging off a tree over a drop onto rocks, it was just what I needed. Earlier this year, after months of working on my upper body strength, I was proud that I could do an unassisted pull up. Yet thanks to adrenaline, in this situation I was able to pull myself from hanging off the tree to sitting in it, all with the heavy pack on my back and without even a grunt of effort.

Work stress makes us feel like we’re hanging off that tree over a drop and there’s nothing we can do. Many of our work environments are set up to push those stress buttons, to make us rush around on the edge of panic, to convince us that these decisions we’re making or that others are making for us, are life and death. Indeed, the decisions that are made at the top of the organisational hierarchy can feel like life or death to those of us below because they threaten our livelihoods. They threaten the relationships we’ve built at work. They threaten our sense of who we are and how much we are valued. The feeling is constant. There’s no simple fix to the situation, yet the stress hormones are surging round the body, insisting that death is just there and you need to act now!

We can certainly work on our stress responses and learn to manage our reactions, but here’s the rub. If we work to reduce how much our work means to us in order to reduce the stress it causes us, it will mean we’re less engaged and put less effort in, which is the exact opposite of what employers generally want from us. So yes, let’s learn to manage our stress responses, but let’s also continue to demand that our employers provide us with a safe and healthy workplace that doesn’t constantly make us feel like we’re hanging off a tree over a cliff.

Always note the good things

We all know that bad things often seem to outweigh the good when we’re reflecting on life. Losses affect us more than wins, bad experiences have a bigger impact on us than good. Research has even shown that bad things seem to be 3-5 times stronger than good in affecting our happiness.

Yet with my falling down the bank incident, there was so much that could have been worse or that actually went well, I can’t help feeling incredibly lucky. I survived it with only some bruising and scratches. I didn’t even lose anything: nothing fell out of my pack, my hat and one walking stick stayed up on the track, while the other stick landed right by my hand while I was hanging off the tree so I could easily scoop it up again. The friend I was tramping with knew exactly what to do and found a safe way to get to me. That tree I grabbed was in just the right place to save me from a potentially nasty drop. We got back up on to the track with relatively little drama. And I even got to eat my emergency chocolate.

It may seem like this tramping trip was a “bad thing” but overall I loved it. The sheer amount of space that is created when there is no contact with the outside world is remarkable. The peace of being in nature, of having no demands on me other than the basic physical requirements of moving, creating shelter and making food was refreshing in a way that weeks of holidays have not been in the past. The cosiness of lying cuddled up in a sleeping bag while it was freezing outside the tent, the sounds of the fantails as they accompanied us all the way along the track … It felt significant, like a break point with a previous way of living. Like all experiences, it is fleeting, but I’m hoping I can hold on to it as I make my way back to my normal everyday life.